FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

The Artist in Residence Program at Recology San Francisco is thrilled to announce exhibition dates for current artists-in-residence Nimah Gobir, Nasim Moghadam, and Stanford University undergraduate Bhu Kongtaveelert.

Friday, January 24, 2025 from 5 – 8 PM

Saturday, January 25, 2025 from 12 – 3 PM

Tuesday, January 28, 2025 from 5 – 7:30 PM with artist talk by Bhu Kongtaveelert at 6 PM (401 Tunnel), Nimah Gobir at 6:30 PM (503 Tunnel), and Nasim Moghadam at 7 PM (503 Tunnel).

Admission is free and open to the public – no reservation is required. All ages are welcome and the site is wheelchair accessible.

Location

Recology Art Studios

503 and 401 Tunnel Avenue, San Francisco

Nimah Gobir

Nimah Gobir

So Far, So Good

Written by Weston Teruya

While seeking material evidence of Black cultural life as a resident artist, Nimah Gobir’s curiosity was piqued when she encountered a few black & white photographs of an anonymous Black woman spending time at the beach with a white family in the 1940s, posing with them during a pause in swimming and playing in the sand. These precious few images were tucked within a decades-spanning album of the white family’s photographs–a seemingly brief intersection of lives. So Far, So Good grew out of a speculative investigation into this woman’s unknown story, the possible record of her loved ones, joys, concerns, and home, as told through images and imagined ephemera from her life. In Gobir’s other work, she often expands on her own family archives, creating paintings that reference photos and images of loved ones that she knows intimately. The act of image making serves as a remembering and tenderness; the honoring of beloved stories and people. Here, Gobir works from an outside position, parsing through assembled visual cues to decipher relationships and imagine the fullness of an unknown person’s story. She filled in details using other found materials, including photo transfers drawing upon another family’s home garden photos and historic research into Black familial archives from the period. She also brings personal textures to the work, embedding references to her relatives, like bags of oranges that evoke memories of her grandmother’s love of farmer’s markets and gestures of care in the form of food. Each person’s home is its own universe and here Gobir proposes the household that the woman in the photographs might have created for herself and her loved ones.

While the exhibition expands on these found photos, Gobir does not propose this speculative portrait as something definitive or comprehensive–that might be mistaken for a truth that ends up displacing the hidden story of a very real person. Through outsized installation elements and layered surfaces of her paintings and textiles that speak to an assembly of disparate sources, Gobir gestures toward this being about the process of imagining and recovering memory, more than the narrative of a specific woman. Oversized industrial spools, large scale fabric threads, and vacuum cleaner cords winding between them, evoke the narrative threads she has sewn and pieced together.

Even a seemingly more complete family photographic archive cannot describe the wholeness of a complete life, the moments outside of photo-ready highlights. How do we create space for stories and connections that are not materially available and outside of our immediate relations; whose traces can only be found in passing, buried amidst other people’s records? For people whose collective stories are missing from the historic record, the act of imagining is a community process of found kinship and empathy on the way toward recovery and repair.

The colorful and sunny flowery patterns that run throughout the works on view belie the cautious outlook of the exhibition’s title–So Far, So Good–a perspective Gobir uses to describe living in the in-between state of Blackness. Things are ok, but could be better; they might turn at any moment. It speaks to an awareness of history: this is what it means to live with a consciousness of what has come before and what is ahead. The phrase carries an undercurrent of concern, but a stubborn desire to find ways to collectively create community sources of joy and comfort. Home is not a static place, it is a space that is made and remade, opened up, and where stories can be imagined.

Nimah Gobir is an artist and educator based in Oakland whose work explores how she came to inherit the complexities and nuances of her Black identity from her family. Gobir completed her undergraduate studies at Chapman University with a B.F.A. in Studio Art and B.A. in Peace Studies. She has an M.Ed from Harvard Graduate School of Education with a focus in Arts in Education. She has exhibited at the Museum of the African Diaspora, SOMArts, The Growlery, Johansson Projects, and Root Division where she was awarded the Blau-Gold Studio/Teaching fellowship. She was recently granted the 2024 Tournesol Award and is an artist-in-residence at Headlands Center for the Arts.

Nasim Moghadam

Nasim Moghadam

Echoes of the Shattered

Written by Weston Teruya

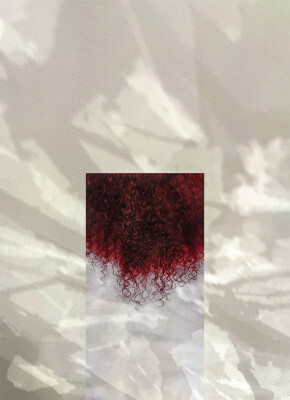

In Echoes of the Shattered, Nasim Moghadam utilizes photographic portraits and fragmented mirrors to consider how women navigate the world in their identities and find agency over their bodies and how they are perceived. The duality in her title–both ripples and sharp punctuations–thematically carries across her project. Her use of mirror fragments throughout the space simultaneously references the transcendence and geometric intricacy of Iranian architectural mirror work–light bounces in illuminated webs across gallery walls–and evokes an underlying vulnerability or potential hurt evidenced in rough broken glass edges. In some of her photographs, a woman’s figure is draped in a dark, satin fabric that at moments appears devotional and in others, suffocating as it pulls across her face.

At the center of the gallery, she suspends a large textile-like piece comprised of finely cut mirror fragments threaded together with thin hand-twisted barbed wire in a repeated eye pattern. In viewing the work, we are inescapably faced with our own fragmented image across the surface–as we look, we are looked at and asked to repeatedly consider our own viewership. On the reverse side of the piece, Moghadam has printed an image of a woman covering her face with her hands, almost as if in mourning or exhaustion. We move between contrasts of seeing and obfuscation, being seen and a woman refusing to be perceived, eyes open and covered. Mirrors give a sense of illusory space–we might think that we see what is through the glass surface, but our vision is turned back on itself. By hanging the piece in space, we are invited to literally step behind and consider what is typically unseen and underneath.

In other mirrored works in the exhibition, glass surfaces appear to tumble from rough breakage to clean cuts and melted puddles–edges transition in a gradient from jagged glass with flaking silvered backing that appears to have been struck with violent force, to delicate and polished cuts that mimic the pattern of fragmentation. Her attention to these details suggests a simultaneity and social complexity rather than binaries. Women face social pressures and state control over their bodies but also participate within and resist these dynamics.

As in many of her projects, Moghadam utilizes a pared-down selection of materials to invite close consideration of the details and her sensitivity to craft. She acknowledges pain and societal wounds but decenters it as an overdetermining force through her formal artistic choices. There is softness and beauty in the broken and a calm that comes from an underlying sense of justice

Nasim Moghadam, a multidisciplinary installation-based artist, explores discrimination, hyphenated identity, and the constraints placed on women, their bodies, and their voices, crafting narratives inspired by global endeavors for women’s unalienable rights.

Born in Iran, Moghadam holds an MFA from the San Francisco Art Institute and serves as an Adjunct Professor at California College of the Arts and Foothill College. She has earned awards from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts, the H.A.R.D. Foundation, and the Outstanding Graduate Award from SFAI. She has also received fellowships and residencies at Kala Art Institute, Cubberley Artist Studio Program, and Building 180.

Her works have been showcased at international festivals in Italy, Japan, and New York, as well as venues such as SFMoMA’s Soapbox Derby, SOMArts, the San Francisco Art Commission Gallery, the Museum of Craft and Design, Southern Exposure, Minnesota Street Project, Aggregate Space, Root Division, the Kala Art Institute, Soil Gallery and the O’Hanlon Center for the Arts.

Bhu Kongtaveelert

Dead Letter Office

Written by Weston Teruya

In Bhu Kongtaveelert’s immersive installation, Dead Letter Office, the artist makes clear that people’s decisions to migrate don’t start or stop at borders. Through his creative process, Kongtaveelert highlights the ways that the cheap, discarded goods and materials he sourced from the Public Reuse and Recycling Area at Recology while in-residence are allowed to move across national boundaries from places like China, Vietnam, Brazil, or Honduras.

A dead letter office is the postal department where undeliverable mail is held and processed; space of temporarily arrested transition, similar to the pile at Recology itself, where discarded things are sorted and re-routed. At the entry to the exhibition space, audience members are faced with their own interstitial moment as they are asked to navigate back and forth through a series of crowd control stanchions before they can see other works on view, including a series of objects with their country of origin labels visible, an office cart, and a series of sculptures and animations. The installation contains a polyrhythm of circulation and stoppages, delays, and acceleration.

A major centerpiece of Kongtaveelert’s project is a large crate containing projectors that shine on sculptural assemblages along the walls. These mounted pieces are mostly comprised of wire mesh, grillwork, bed frames, and lattices–layers of crisscrossing hard line patterns. In some areas, he weaves film stock and other material through and across grates and frames. Laid across one another, the metal lines of each grid interrupt one another’s sense of order. These objects can serve as gestures of affection and intimacy for loved ones at a distance. The crate at the center suggests a balikbayan box–duty-free care packages sent by overseas Filipinos to their families back in their island hometowns. In another corner of the gallery, Kongtaveelert displays a video documenting a conversation between himself and his mother in Thailand as she opens a package he sent home over the holiday season when he could not be there in person.

Bhumikorn Kongtaveelert is an artist working in painting, immersive installation, and systems thinking. He is currently pursuing degrees in Computer Science, Art Practice, and Earth Systems at Stanford University. Outside of class, he engages in research related to the bureaucracy and technology of funding local climate-resilient infrastructure. He works with a youth-led international mentorship program for Southeast Asian students, “Southeast Asia Exchange,” to facilitate panels on Climate Migration and Traditions and Modernism in Southeast Asian art. Kongtaveelert was a 2022 and 2023 recipient of Stanford’s Institute for Diversity in the Arts (IDA) fellowship and previously exhibited at Stanford Art Gallery, Kearny Street Workshop and Et al.

About the Artist in Residence Program

The Recology San Francisco Artist in Residence (AIR) Program, a part of Recology’s Sustainability Education Program, is both an art and education initiative that provides Bay Area artists with access to discarded materials, an unrestricted stipend, and individual studio space. During their four-month residency at the San Francisco Transfer Station, artists create a body of work and host studio visits for children and adults, fostering public awareness about the importance of preserving natural resources.

Since 1990, over 160 professional artists and 55 student artists from local universities and colleges have participated, working across disciplines—including new media, video, painting, photography, performance, sculpture, and installation—to explore a wide range of topics.

The program also strives to cultivate a more diverse and inclusive residency, amplifying perspectives from Bay Area communities and inspiring visitors of all ages to reimagine their role in building a just and sustainable world.